No products in the cart.

Web-Based Supply Chain: potentialities, challenges and research opportunities

Author: Mokhtar Amami

The web technology holds a great potential in supply chain management. Strategic advantage can be accomplished through the integration of the web-based processes in the organization’s core supply chain. It will not only reduce costs, but it will also create value along the supply chain for all networked partners. By allowing all partners (inside and outside organizational boundaries) to access the same information online, the web supply chain optimizes the demand chain, improves collaboration, and ensures synchronization across customers, suppliers and alliance partners. However, these great potentialities carry four major challenges to researchers and managers. In this limited space we try first to characterize the web-based supply chain (by contrasting it to the traditional supply chain) and outline these challenges and highlight research opportunities.

1. Web–based supply chain

The traditional supply chain is still embedded in Porter’s value chain model (Porter and Millar, 1985), which is based on value-adding members. The web-based supply chain does not look like a chain of value-adding members; on the contrary, “it looks like a web of virtual enterprises that behave as living ameba-like organisms – constantly changing shape, expanding, shrinking, multiplying, dividing, shifting, and mutating” (Andrews & Hahn, 1998).

Two forces of equal importance are reshaping this emerging supply chain: (a) perpetual changes in the roles of supply chain members, which subsequently and almost inevitably result in power shifts within the traditional supply chains; and (b) customer/consumer preference for personal customization and quick gratification, encouraging the web-based supply chain members to surround their joint customer(s) in new and exciting ways. Combined, these forces are helping to transform traditional value chains into web-value chains. This transformation is gradual but is accelerating in speed and fuelled by advances in web technology. Within a web value chain, each virtual enterprise looks like a mini-web of its own, encompassing all of its businesses (including joint ventures and subsidiaries) and partners – thousands of strategic, tactical, and virtual partners and suppliers around the world, spread over many tiers.

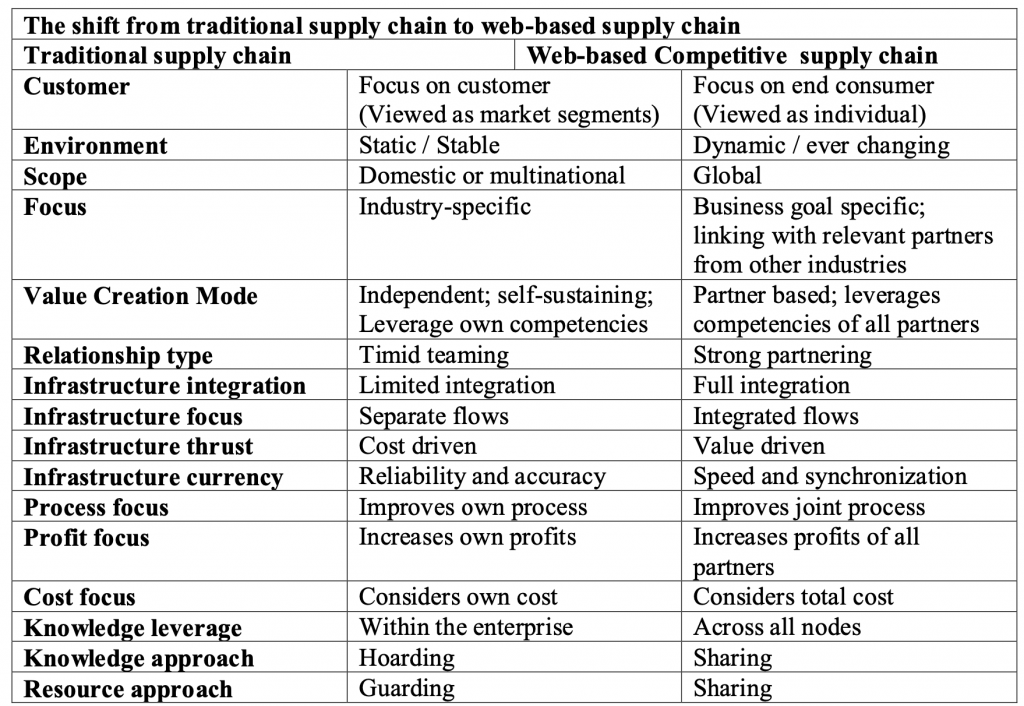

The new web-based supply chain will be more complex. The complexity stems from the new dynamic that “deverticalizes” the old supply chain, the multiplicity of SKUs, and the lack of standard metrics. The traditional supply chains are a collection of heterogeneous sets of agents (each) acting on the basis (typically) of incomplete information. The driving motivation is usually local (e.g., maximizing local profit or local efficacy). Efficacy and value creation along the chain are not the major focus. The movement of information and material is slow because of problems associated with data formatting and integration, applications compatibility, lack of metrics and other managerial and organizational barriers. However, the new environment is imposing new competitive dimensions: responsiveness and flexibility. The ubiquity of the organizations and consumers. Content and interaction, two dimensions of traditional supply chain channels, are antiquated and will be replaced by channels that build and maintain relationships based on awareness, accessibility, and responsiveness. The vertical-tunneled supply chain model will be abandoned and substituted by a web-based supply chain characterized by dynamic structure, constant adaptive agents, nonlinearities and feedback. Table 1 contrasts and summarizes the shift from traditional supply chain to web-based supply chain (WBSC).

Table 1: Traditional supply chain and Web-based supply chain Characterization (Adapted from Andrews, P. & Hahn, J.; 1998).

WBSC is complex and dynamic. It is characterized by incessant change of transactions, relationships, and infrastructures. It tends to support a great number of Stock Keeping Units (SKU) (that may prevent demand optimization), and order driven lot-sizing to capacity availability booking and involves multiple enterprises. Furthermore, the emergence of the WBSC is a natural response to the new demanding customer (Blackwell et al., 2001), the new dynamic environment and heightening competition. The WBSC must be designed to support the fulfillment of customer orders for customized products and services faster and more efficiently than competitors. Consequently, it is critical to focus researchers and managers alike on the challenges and opportunities of this emerging WBSC.

2. Challenges and research opportunities of the web-based supply chain

The literature on the challenges and research opportunities of the new emerging of web-based supply chain is still relatively modest. Our contention is that the management of the web-based supply chain requires four imperatives. The first imperative is to develop new and better models that allow modeling the new dynamic environment. The second imperative is to develop web- based infrastructures to develop and enhance understanding and trust. The third imperative is to develop better metrics that allow supply chain visibility and foster eCommerce expansion. The fourth imperative is to develop and use software agent technology to help synchronize operation, share information, and ensure dynamic configuration.

2.1 Modeling the dynamic competitive environment among web-based supply chains.

Traditional research in the field of the supply chain focuses on optimization of vertical networks. This traditional research studies the cooperation and coordination among partners along the supply chain, without considering horizontal relationships with competitors. Each core player can build his own vertical supply chain and draw a kind of boundary that may somewhat shield his up-stream and down-stream networks from environmental turbulences. The strategic competition is conducted as supply chain against supply chain (Toyota supply chain versus Ford supply chain, Dell supply chain versus HP supply chain, etc.). The development of Internet technology and the emergence of the web-based supply chain have changed this established paradigm. As a result of decreasing coordination costs and other factors such as an increasingly demanding customer, compressed cycle times and faster rates of innovation, each core player and his partners along the supply chain (vertical supply chain) become involved in horizontal relationship with other competitors in different supply chains and compete for resources and markets. The new emerging paradigm considers that partners in a vertical supply chain are not shielded individually and collectively from strategic decisions of other core players and their partners in different supply chains. The study of this new interaction extends supply chain management research into new directions and may yield promising insights to managers. The main objective of these new research opportunities is to understand the dynamic nature of web- based supply chains. Studying the dynamics of this new environment will allow the derivation of partial equilibrium and disequilibrium conditions of new web-based supply chain players (Dafermos, 1980; Dupuis & Nagumey, 1993; Geoffrion & Power, 1995; Nagumey, 1999).

2.2 Web-based supply chain and trust

The sources of supply chain risks and uncertainties are multiple. These sources may arise from over-reactions to external or internal events, unnecessary interventions, lack of visibility, distorted information throughout a supply chain, and mistrust. The financial consequences of these risks and uncertainties can be enormous (e.g., Inventory costs due to obsolescence, markdowns and stock-outs, etc.). As stressed earlier, a web supply chain must be responsive to changing market trends, customer preferences and dynamic network supply chains. Mutual trust may be viewed as one of the primary factors that will reduce risks and uncertainties, and lead to web supply chain efficiency. The trust is based on the “willingness to be vulnerable to the actions of another party based on expectations of trustworthiness” (Mayer et al., 1995). In the supply chain field this trust takes the form of having confidence in aspects such as order cycle time, order status, demand forecasts, suppliers’ capability to deliver, manufacturing capacity, quality of the products and services delivered.

To improve web supply chain performance, dyad or collective trust must be established and developed. Mutual trust can minimize inventory (as a buffer against risks and uncertainties), reduce lead-time and the impact of bullwhip effect (Lee et al., 1997), and increase visibility, which in turn will enhance further trust. For example, a supply chain partner that has detailed information and knowledge of the real picture (about finished goods inventory, material inventory, work-in-process, actual demands and forecasts, production plans, capacity, yields, and order status) in each part of the web chain can make better decisions, and consequently, improve the performance of the web supply chain. Thus, building and developing mutual understanding and trust will yield better outcomes.

| Supply chain outcomes | Impact of mutual understandings and trust |

|---|---|

| Minimizing inventory | Sales are not driven by over orders holding inventory for key customers, and hedging against the risk of stock-out |

| Winning orders | Over quoting on delivery times to customers is minimized which translated in winning orders |

| Customer loyalty | Accurate information reduces the gap between customer expectation and supply chain capability and thus increases customer loyalty. |

| Cooperation among supply chain partners | Increases cooperation among managerial functional areas (such as between marketing & engineering) in each enterprise and consequently interorganizational relationships |

| Efficient operation of supply chain | Accurate information and transparency of demand along the supply chain improve operation efficiency for each partner and for the whole supply chain |

Table 2 highlights business areas where mutual understanding and trust can improve outcomes.

There is a real need for developing a web-based supply chain framework for building, developing and enhancing trust. How do we use the web for building, developing, and enhancing trust in order to extend the web supply chain and eCommerce? Little theory-guided research has been conducted in developing web-based computer systems to enhance trust and shared understanding among businesses and between businesses and customers who are willing to be part of the web-based supply chain. A promising research opportunity involves the building of a theoretical framework for enhancing trust and shared kind of understanding. It also involves the design and the development of a web-based interactive information system for enhancing trust, which aims to support the generation of shared understanding and trust.

2.3 Metrics for controlling the web supply chain performance.

Agility and responsiveness are two key requirements to meet demanding consumer. The web- based supply chain needs metrics and control mechanisms for monitoring performance. In the traditional supply chain where competition is supply chain against supply chain, the core player (pivot) plays a major role in coordinating activities along the supply chain, hence controlling and monitoring performance. Moreover, the actual fragmentation of the supply chain software market is acting as barrier for integration and for virtual partnerships.

Developing and using web-based supply chain (WBSC), characterized by pervasive technologies, requires an extended paradigm. This new extended paradigm must go beyond linear chains to encompass mechanisms for real-time consumption monitoring, mechanisms for virtual manufacturing coordination, and metrics for visibility, responsiveness, and velocity. It must also encompass infrastructures, approaches and models for supporting virtual partnerships and integration.

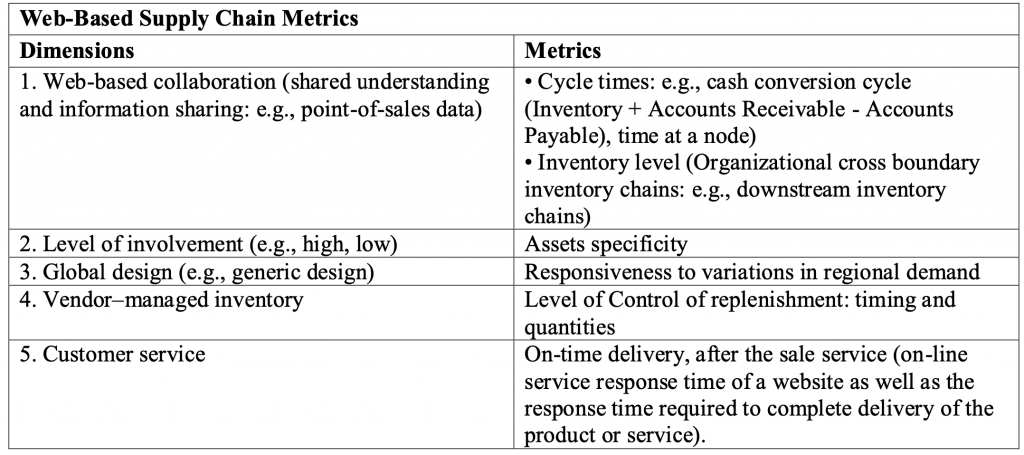

Web-based supply chain needs to perform on three key dimensions: a) service, b) assets, and c) speed. Service dimension encompasses the capability to anticipate, capture and fulfill customer demand with customized products and services that meet the required lead-time. Asset’s dimension consists of all assets that have actual and future value, particularly inventory. Speed dimension encompasses metrics that track visibility, responsiveness, and velocity.

Table 3 shows a few metrics for the WBSC that embody supply chain metrics already developed or suggested in the literature.

Table 3: Web-based supply chains metrics

Organizations that intend to take advantage of the WBSC to meet end-customer requirements must develop supply chain performance measures that are designed to support and monitor activities across organizational boundaries and chains. Moreover, the design and development of these metrics will enhance and support eCommerce expansion.

Metrics cannot be considered in a vacuum. They should fit the value proposition of the web- based supply chain, in other terms they must be aligned with the intent and objectives of their business strategies. It is imperative that business strategy and the supply chain strategy must be aligned to ensure efficient execution. This area of research is a fertile ground for developing new metrics for measuring the emerging web supply chain performance.

2.4 The use of software agent technology to support web supply chain management.

Anderson and Lee (1999) pointed out that supply chain boundaries are no longer confined to the traditional boundaries of an organization. The emerging web supply chain, with its inherent focus on web-enabled interaction and collaboration among supply chain partners, will be a major driver of a sustainable competitive advantage. Although systems such as EDI technology, ERP and CRM play a major role in coordinating supply chain entities, software agents could be more effective in coordinating these entities, particularly in a dynamic environment. The research challenge of software agents consists of analyzing and understanding the precise role of this technology and identifying the implementation problems and risks associated with it.

The development of web technology fostered electronic commerce is creating huge potentials for consumers and businesses to enhance interaction in new markets (electronic marketplaces). The use of the web allows search cost reduction, product selection and ordering, online delivery of digital products and services, and mass customization. It also allows information sharing, collaboration, and planning among supply chain partners. However, the use of the web remains a labor intensive and time-consuming business. A higher level of coordination among web supply chain partners requires a new system that supports today’s dynamic environment. Software agents therefore offer multiple opportunities to support the evolution of web supply chains.

Characterization of Software agents: Software agents are entities that can operate autonomously on behalf of the user. In this perspective, the technology is expected to handle many automated supply chain processes and perform many tasks on behalf of their users. They can interact with other agents through a communication network without the intervention of the owner. They also can perform tasks asynchronously and adapt dynamically. Three main characteristics are often cited as a rationale for adopting software agents: a) data, control, expertise, or resources are inherently distributed; b) the system is naturally regarded as society of autonomous cooperating sub systems; and c) the system contains legacy components, which must be made to interact with other, possibly new sub systems.

The emerging web supply chain fits these three main characteristics. A web supply chain is a web of virtual enterprises that have their own resources, capabilities, tasks, objectives, and strategies. They engage in a dynamic cooperation to fulfill common goals and their own interests. Systems developed to coordinate among virtual enterprises are still in their infancy. Software agent technology can be used to support collaboration among partners in the new emerging supply chain management.

Using software agent technology to support collaboration among web supply chain partners: Collaboration is a critical success factor for achieving sustainable competitiveness. A web supply chain involves a great number of partners who are “constantly changing shape, expanding, shrinking, multiplying, dividing, shifting, and mutating” (Andrews & Hahn, 1998). It requires that partners synchronize their actions to increase total supply chain value. To avoid distortion and conflicts among these partners, software agents may be used to support dynamic collaboration. Three main areas of collaboration may be supported by software agent technology: a) information sharing; b) virtual synchronized operation; and c) dynamic configuration.

Information sharing consists of codified information sharing and knowledge sharing. The former, which is transactional by nature, can be exchanged using EDI technology. The latter requires a higher level of support that can be performed by software agents. For example, searching, cross boundary communication and access control requires respectively searching agents, interface agents, and authorization agents.

Virtual synchronized operation among virtual enterprises goes beyond short or long-term contracts or agreements. It tends to reduce uncertainties through information gathering and delivering warning information to the affected location for appropriate action. Software agents can play a major role in gathering and delivering this kind of information. For example, to synchronize the production schedule, a software agent can engage in negotiation with other agents to resolve conflict and to make appropriate adjustment through real time scheduling.

Dynamic configuration aims at responding to customer needs and effective use of resources. The main outcome of the dynamic configuration process consists of determining the entities in the supply chain that can design specific processes and performing the required activities that can deliver product to consumer at the optimum cost (Anderson & Lee, 1999). Software search agents can be used to search potential partners through electronic markets. Software matchmaker agents can be used to match buyers with suppliers based on mutual interests and capabilities. Software auction agents and software negotiation agents can also be used to structure the process of delivering product to consumer better than competitors.

Software agent technology can provide automated and customized services to customers. Through information sharing, synchronized operation and dynamic configuration, agent technology can support the emerging web supply chain. It is imperative that supply chain researchers devote more attention to this emerging field.

Conclusion

In this blog, we argued that dynamic structure, constant adaptive agents, nonlinearities, and feedback characterize the emerging web-based supply chain. We have identified and briefly reviewed four main research opportunities and challenges related to the emerging web supply chain: a) modeling the dynamic competitive environment among web supply chains; b) web- based supply chain and trust; c) metrics for controlling the web supply chain performance; and d) the use of software agent technology to support collaboration.

In the research area of modeling the dynamic competitive environment among web supply chains, we suggest that deriving partial equilibrium and disequilibrium conditions of new web- based supply chain players will help to understand the dynamic nature of web-based supply chains. In the research domain of web-based supply chain and trust, we also suggest that enhanced trust and shared understanding may be generated by designing and developing a web based interactive information system for enhancing trust. In the research domain of metrics for controlling the web supply chain performance, we argue that metrics should fit the value proposition of the web-based supply chain, in other terms they must be aligned with the intent and objectives of the underlying business strategies. Consequently, it is imperative that business strategy and the supply chain strategy must be aligned to ensure efficient execution. Finally, we suggest that software agent technology should be used to support the collaboration required among web supply chain entities. Information sharing, synchronized operation, and dynamic configuration are three areas where agent technology may be used to deliver products to consumers cost effectively.

References

Anderson, D. L. & Lee, H. (1999), “Synchronized supply chains: the new frontier”, 1999, (1/4/99) ASCET Volume 1, http://www.ascet.com/documents.asp?d_ID=198

Andrews P. & Hahn, J. (1998) “Transforming supply chains into value webs” Strategy & Leadership, Vol. 26, No 3, pp. 7-12

Blackwell, Roger. D. & Blackwell, Kristina. (2001), The Century of The Consumer: Converting Supply Chains Into Demand Chains, Supply Chain Yearbook, 2001 Edition, McGraw-Hill, 2001. Dafermos, S. (1980), “Traffic Equilibrium and Variational Inequalities,” Transportation , Vol.14, pp.42-54.

Dupuis, P., & Nagumey, A. (1993), “Dynamical Systems and Variational Inequalities,” Operations Research, Vol. 44, pp.9-42.

Geoffrion, A.M., & Power, R. F. (1995), “Twenty Years of Stategic Distribution System Design: An Evolutionary Perspective,” Inferfaces, Vol.22, pp.105-127.

Lee, H., Padmanablan V. & Whang, S. (1997), Information Distortion In A Supply Chain: Bullwhip Effect, Management Science, Vol. 43, No. 4, pp. 546-558.

Mayer, R.C., Davis, J.H., & Schoorman, F.D. (1995), ”An Integrative Model of Organizational Trust”, Academy of Management Review, Vol. 20, No. 3, pp. 709-734.

Nagumey, A. (1999), Network Economics: A Variational Inequality Approach, second and revised edition, Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht, The N etherlands.

Porter, M.E. & Millar, V.E. (1985), “How Information Gives You Competitive Advantage,” Harvard Business Review, (July-Aug.), pp. 149-160.